The Rationale of Mythology

Introduction

We are used to talking of myths in ‘past tense’. To most of us, myths are stories of the archaic man that have little relevance in this age of reason and logic. Yet for some inexplicable reason, one fine day Lord Ganesha decides to drink milk. A semi mechanical monster – called the monkey man keeps the residents of Delhi awake for many nights (same way as a hybrid creature Sphinx had terrorized the ancient Thebes). In his war against terror, the President of America constantly used the Biblical construct of ‘good over evil’ while addressing his nuclear age commandos. And not so much in the past, a political party swelled from a meager two-member presence to fill a large part of the Indian parliament. Riding the rath of Ramrajya.

There is something about myths that doesn’t let them die. Myths are not History. They are here, and everywhere, in one form, or another. In mythological serials on televisions, in action stories of Hollywood, in the need of human beings to clone themselves and the entertainment value of the computer game that you play everyday.

The purpose of this study is to understand the system of mythology, better. What about them makes them connect with people across time and space? In what form are myths a part of our lives? What are the patterns, structures, themes and archetypes that the body of mythology operates within? And in what ways can we use this knowledge to connect with people at a deeper level? This article will attempt to successively de-layer the complexities of the subject. Welcome to the ‘Hero’s Journey’!

Universality in Myths

Scene this – the hero of an action movie, a nice guy going about his daily routine, gets challenged into a brawl with the area’s don. The occasion could be a refusal to pay the ‘haftaa’, saving a child from being kidnapped or protecting the ‘izzat’ of the heroine. Obviously the hero wins. Gets an offer from the don of the underworld to work for him. Refuses the offer. But as incidents would have it, violence strikes his home. This could be the rape of a sister, murder of a friend etc. The hero joins the mayhem. Fights evil restores order. Repents for his sin (getting hospitalized, serving rigorous imprisonment – baamushakkat kaid). Comes back to begin a new life, sings the title song, kisses the heroine. The end.

This could be a plot of Amitabh Bachchan’s Zanjeer; Manoj Bajpai’s Shool, or Lucas Films’ Star Wars. Joseph Campbell outlined a structure for the hero’s journey in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. The structure was based on a universally satisfying pattern found in myths. From the Iliad to the Odyssey, from Zanjeer to Star Wars, from Ram’s vanvaas to Budha’s journey, the structure seems to work. It flows like this:

The Ordinary World – The Call to Adventure – Refusal of the Call – Mentor (The Wise Old Man or Woman) – Crossing the First Threshold – Tests, allies and Enemies – Approach to the Inmost Cave – The Supreme Ordeal – Reward – The Road Back – Resurrection – Return with the Elixir

Myths across cultures appear to report identical patterns and structures. These patterns are universal, as they seem to work across time and geography. Not only is there a marked similarity in myths of various cultures. These archaic myths have also manifested themselves in modern times through modern means. Besides being present in today’s society in the form of traditional rituals and symbols. What explains such universality and undying spirit of myths?

The key to their universality and continuity perhaps lies in the very idea of myths. The belief that myths are a response to deep instinctive human desires. Despite the differences in their viewing lenses (Structuralism, Anthropology, Sociology, Religion or Culture) mythologists cannot negate the ‘need responsiveness’ of myths. The subject matter of myths further corroborates this theory. Across cultures, myths deal with fundamental human concerns as the quest for origin, nature and its elements, man-woman relationships, forms and functioning of animals, morals of living, life after death etc. Even the language of the myths is highly intuitive and reflects the deepest hopes, fears, anxieties, dreams, desires and fantasies of man.

“…The unconscious and the infantile dimensions of the inner life (preoccupations with birth, death, bodily functions and the pleasure or guilt associated with them, sexual organs and sexual feelings, and relationships within the family) elaborated and legitimated through the decorum of symbolism and artistry, they are the basic stuff of mythology.” Sudhir Kakkar, The Indian Psyche

Dealing with common human concerns and needs, its only natural that the body of mythology should report a sense of universality. What we have as a result is a pool of themes and archetypes that enjoy universal human appeal. What follows is a sojourn into these universal themes, the needs they fulfill and the way we experience them in our everyday lives.

Recurrent Themes

Escaping Mortality - Myths of Time

The inevitability of death would have been a psychological challenge for the archaic man. It still is for us. The realization that his existence on this earth was finite and historical, that he was the ephemeral in this permanent creation would have been a subject of much disillusionment.

It has been his endeavor ever since to beat death and its finality – a deep desire to escape this inevitable becoming. Myths of time help reconcile this disillusionment of finite existence. By creating the concept of immortal time.

Across cultures myths talk about the ‘primordial’ or ‘sacred’ time. This is the time when supernatural events took place. A definition of time, that is different from the current one. This is the Satta Yuga in Indian mythology and BC in Christianity. Similarly, there are myths of life after death. Which talk about a re-union with the primordial substance in Hindu mythology and the Kingdom of God in the Christian mythology.

Myths of after death existence and primordial time seem to serve the same purpose. They allow man to be a part of a larger scale of time, a part of infinite time. The finite historical living becomes infinite. Death is suddenly not the final end.

By creating immortal time, time myths allow man to escape mortality. They give him a psychological mastery over time, to escape the current duration and move into other rhythms, to live a history, different than the real one.

But the fear of death did not end with the archaic man. As the fear of mortality continues, so does the desire to beat it. It may not be a mere coincidence then that the most engaging activities of today’s man are about looking death into its eyes.

This might explain why spectacles such as car racing, WWF and bull fighting enjoy such entertainment currency. Mircea Eliade likens these methods of entertainment to the concept of primordial time. According to him, both are about scooping out of a fixed duration from linear, historical time. Involving a concentrated time of heightened intensity when paranormal events happen. About living the moments of unreality. There is little surprise then that the most awaited feature at any Indian mela or circus is not any dance item but the ‘wheel of death’ popularly known as ‘maut ka kuan’. Similarly, the most popular of the computer games are those that are about killing and getting killed and coming back to kill again. One game, but ten lives!

The modern man’s method of escaping mortality is visible in his scientific pursuits as well. What else would explain the enormous efforts put behind cloning human beings, while more than half the world lives without basic medical services?

The most popular means of entertainment, such as watching films or reading books too are the modern day substitutes of time myths. Submerging oneself in a film for three hours where life unfolds in another world is an act conceptually similar to the myths of time.

Celebrating Newness - Myths of Creation

Adjacent to the theme of primordial time, most cultures talk about a periodic repetition of creation. The idea of Noah and the flood in Christian mythology or the cyclical creation and dissolution in Indian mythology are the better-known examples. According to the Indian mythology, each day of Brahma begins with srishti (creation) and ends in pralaya (dissolution).

The myths of periodic repetition of creation point to an intrinsic human need for fresh beginnings. The creation myths are in effect rejuvenation myths. They point towards a deep desire for the world to be renovated. The need to be a part of a new History in a world created afresh.

This need for a new canvass is apparent in the hope and expectations with which we celebrate the beginning of a New Year. Not surprisingly, of all the events in the recent past, the beginning of the new millennium has been the biggest grosser for the marketing and event management fraternity. The myth manifests itself every-time we celebrate childbirth or entry into a new house ritualized as ‘griha pravesh’.

The most prominent festival of newness however is Diwali. A time that witnesses a boom in the sales of paints, cars, houses, utensils, clothes and all other significant purchases. Diwali is also the time to begin new ventures for most Indian entrepreneurs.

Similar to the myths of creation are the fertility myths pointed out by Sir James Frazer (The Golden Bough). Fertility myths are the myths of dying gods who take rebirth to bring a new life to the community. The inherent theme of fertility myths is the vegetation cycle and its need for cyclical regeneration.

In an agricultural society like India, the new beginnings seem naturally aligned to the agricultural cycle. For it cannot be mere coincidence that Baisakhi, Makar Sankrati and Pongal are simultaneously the new year and the harvesting times of the North, Central and South India. That’s a classic confluence of the creation myths and the fertility myths.

The Nostalgia for Paradise – Myths of Golden Age

The idea of paradise may be variable in content. But in concept it’s everybody’s world of perfection. The most common features of paradise across myths of different cultures are immortality, freedom, possibility of ascension into heaven, communication with animals and an access to God himself. In essence, all of what is not possible in the mortal world. This time of perfectness in Indian mythology was the ‘krita yuga’, just as the Garden of Eden symbolized the western idea of paradise.

Myths of Paradise reconcile the human despair with their actual condition and the need to believe that there was a higher purpose to human life. To say that God sure had a higher purpose in mind but the freedom and the abilities were lost by the ‘fall of man’. This fall of man is Adam’s sin in the West or the decline of dharma (the moral order) leading to the kali yuga in Indian mythology. What remains is the nostalgia for the paradise that was lost.

Milton put this nostalgia into words when he wrote ‘The Paradise Lost’. So did Jagjit Singh when he sung “woh kagaz ki kashti, woh baarish ka paani” – a song that created the nostalgia of an idyllic childhood. Bryan Adams invoked the nostalgia of youth in ‘The Summer of ‘69’ and when he sang ‘18 Till I Die’.

It might be interesting to note that in India, childhood is considered to be the Golden Age of one’s life while in the west it is the adulthood. Reason why Jagjit Singh celebrates the nostalgia for childhood while Bryan Adams celebrates adulthood.

Marx’s promise of a classless society was indeed a promise to restore the lost paradise. The manner in which the Communist struggle was projected, the redemptive role of the proletariat, the final struggle between good and evil leading to the establishment of the classless society, made a perfect recipe for the myth.

Closer home, when the BJP talked of value-based politics and promised clean governance, they were actually invoking the myth of Ramrajya – a myth that was in much need for a nation disillusioned with over four decades of fruitless independence.

Restoring Order – Myths of Redemption

This is the myth of the hero – the hero of a celluloid saga, or a mythical tale. The one who comes just when you know he will. This is also the myth of the God hero. Vishnu and Christ are the greatest redeemer myths of all times. The underlying belief is that the supremacy of the order of life shall prevail. That God himself will redeem the mankind from the oppression caused by the loss of order.

Its this need for redemption that leads to Ganesha drinking milk. For Ganesha drank milk because we wanted to believe he did. This is also the need that makes people believe that Gandhi will come back and Christ will be resurrected.

Facilitating Transition – Myths of Initiation

The essential purpose of these myths is to equip for a new life role. Upanayana sanskar in Hindus and baptism in Christianity are but rituals of initiation. Initiation myths come from a belief that you have to die to something in order to be born to another. It’s for this reason that most myths of initiation carry a symbolism of death and re-birth. Dying to something is also to qualify through sacrifice for the membership of the new group. That might explain the reason why most initiation rituals carry an element of sacrifice.

The myth of initiation manifests in our life more by the absence of it. Ragging, smoking, tattooing, piercing are some of the adopted rituals of initiation when the traditional ones have ceased to be practiced. The unprecedented increase in teenage violence in Western countries could also be in some parts attributed to the lack of initiation of children into the civilized society.

Mythic Codes

The above discussion has revealed various themes that have universal and instinctive human appeal and why so. This also establishes why myths will continue to live and find their own means of expression. But this is not the only way myths touch our lives. These stories of Gods and Goddesses, how they lived, what they did, how they were rewarded or punished for their deeds have in effect become a handbook of ‘how to live life’.

The myths of yesteryears are the codes of today’s culture. These ‘mythic codes’ form the skeletal system of the society. Governing people’s sense of right and wrong, good and evil, sin and salvation – the values, which, the society will place its weights on. For instance the ideal of a ‘pativrata naari’ can be traced to the Sita myth, which is a complete guidebook of how a traditional Indian woman should be. Just as the Ten Commandments prescribe the way of life for the Christians who wish to fare well on the Judgement Day.

It is surprising that the mythology of a culture usually has archetypes and myths for all situations and occasions. Just as Sita is the ideal wife, Ram is the ideal elder brother and ruler, Ravana is the classic villain, Krishna is the embodiment of Indian childhood, Eklavya is an ideal student while Lakshman and Bharat are the ideal younger brothers.

An understanding of these mythic codes can be a rich source of motivations. At the same time, care must be taken not to violate these codes in our communication efforts. For any dialing into the heart of a culture can happen only through these codes not against them.

The success and failure of various themes in Indian cinema is an apt example. One of the most widely used themes is the great Dashrath–Ram–Lakshman myth. Films such as Hum Aapke Hain Kaun, Hum Saath Saath Hain, Kabhie Khushi Kabhie Gham have walked to the bank laughing, riding the ropes of this myth from Ramayana. On the other hand the story line of a film like Lamhe could never strike a chord because it violated the ideal Husband / Father archetype.

In fact there are actors / actresses in Bollywood who over a course of several films have been cast into these mythological archetypes. Lalitha Pawar as the quintessential ‘Manthra’, Nirupa Roy as the bereaved mother ‘Sumitra’, Bindu as the ‘Surpnakha’, Renuka Sahane as the ‘Sita Bhabhi’, and Amrish Puri as the ‘Ravana’ may be familiar to the Hindi film buffs.

The construct of a ‘mythic code’ can be explained with some help from Levi-Strauss and his analysis of the structure of the myth. Simply put, Strauss understood myths as a reconciliation of opposites. Which is to say that there are inherent paradoxes in life. For creation, there is destruction, for joy there is suffering, for good there is evil, for salvation there is greed and so on. Myths reconcile these paradoxes. We can understand the product of this reconciliation as the ‘mythic code’.

To illustrate that, the myth of paradise is about the ‘perfect state of being’. This is the mythic code. What the paradise myth reconciles is the despair with the actual condition of human beings and the desire for a better state. Similarly, the Sita myth is the mythic code of the ‘partivrata naari’. What it reconciles is the free willed nature of women and the need for man to control her.

A mythic code can thus be understood as an interaction of inherent contradictions that the myth reconciles. A myth is thus comprised of its component elements. And the dynamic interaction between these opposites lets the myth revive, recast and perpetuate itself. For instance the myth of benevolence of nature reconciles the simultaneous goodness and dreadfulness of nature. And we find this myth to have found fresh relevance everywhere in the form of recycling of paper, Global Conventions etc just when the nature seems to be getting too hostile to mankind. Here the myth is being revived because of a sudden increase in the inherent tension between the components of the myth, namely the increasing dreadfulness of nature. This also explains why the despair with four decades of fruitless independence was just the ripe setting for the BJP to revive the myth of Ramrajya.

Using Mythology

Use of myths in pieces of communication is not a hard to find treasure. Myths through their symbolism have found expression in films and advertisements alike. Wheel a detergent from HLL uses ‘Vishnu’s chakra’ and its connotations. Kerala calls itself ‘God’s own country’ in bid to attract people to the paradisiacal escape. Red & White ads have Aksahy Kumar playing the redeemer. And almost every other Hindi movie has a streak of lightening from heaven concluding the climax scene.

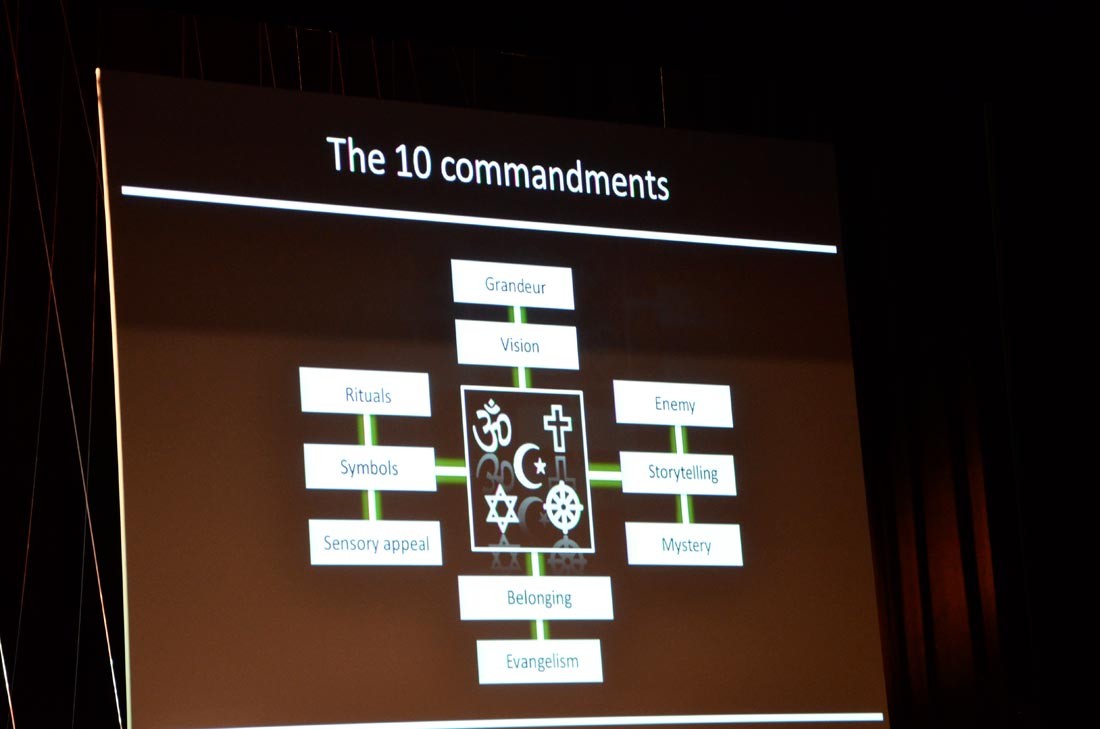

Instances of using myths at a symbolic level are abundant. What remains to be better leveraged however, is the use of mythic codes, for brands to begin to fulfil the needs that the archaic myths fulfilled, to become modern myths.

Brands have already been understood to play a significant role in defining the identity of individuals and community. In a society where, traditional rituals are fading away, brands may become the modern carriers of myths. Brands can hope to provide the same sense of self and identity and rootedness that myths did. Fulfilling the needs of human beings that are psychological and intangible. Reconciling the contradictions that myths reconciled.

More than just associating with the mythic symbols, brands can ride existing mythic codes. What Marx’s Communism did with the myth of Golden Age and what BJP did with the myth of Ramrajya are a few examples. There lies opportunity for a brand like Amul or Mother Dairy to embody the myth of paradisiacal abundance just as Playstation is using the idea of escaping the mortal time. Not surprisingly, the advertising for Smirnoff is a remarkable fit for the product that actually allows you to escape time. And youth brands that are busy creating cults with their own lingo may actually be providing the younger generation with their own rites of passage.

But that may not still be the end of the ways we can use mythology. It seems plausible for instance to use the structure of myths to think brands as myths. To conceptualize brands as constructs that reconcile relative contradictions, just as myths reconcile inherent paradoxes of life. A model to create brand myths may actually lie in this structural understanding of myths. Which of course can be a part of some other paper some other time.

No Comments