Building Youth Brands in a Youthful Country

Introduction

The differences in cultural contexts and economic life-stage of the eastern economies have told us that the way the Asian or more specifically Indian consumers respond to brands, products and other consumption stimulus are many a time different from the well established models of the West. This has now been well recognized and as a result newer or rather more Asian frameworks and ways of thinking have been encouraged in the past decade or so. But are these differences true for youth marketing and youth brands as well? Are the youth in these cultures really so different? Do the time tested western experiences in building youth brands work in such contexts or do we need new frameworks?

The new emphasis in the world of business today is this idea of co-creation. What does youth marketing have to learn from this new way of business? What change in the viewing lenses does this ask for while analyzing consumers and conceiving brands, especially in the context of youth audiences? What about the nature of youth today makes it imminent for brands and businesses to be co-creative with them? How can this approach help us see the world of youth from their side up?

In today’s world of boundariless-ness all kinds of distinctions are blurring. The personal is merging with the professional; entertainment is merging with play and family with friends. More than anybody else, it’s the youth of today who is living their lives like a large interconnected web. How should brands find a place in the lives of the youth whose entire microcosm is web-like and non-linear? How does our traditional brand thinking which is designed for a linear, need gap relationship with its consumer need to re-orient itself?

This paper looks at the youth of India and what does it take to build meaningful youth brands in the country in the light of above mentioned changes. It comes from the belief that any youth brand framework, which works in today’s India must factor in the essential Indian context, the consumer expectation of co-creation and the web-like life that the youth today are living. All this in an attempt to answer two fundamental questions – what does it take to understand youth from their point of view in a social setting such as today’s India and how should a youth brand framework look in such cases?

Youth Vs Youthfulness

Most models and frameworks of building youth brands and mapping youth insights have a western origin. In the Western context, youth was almost always a generation pitted against its seniors. Rebellion was the key starting point. Adventure, music and other symbols of ‘cool’ became a perfect recipe for creating cult brands that rallied against the system. This model of tapping youth presupposes a larger microcosm of youth versus old. It thus preoccupies itself with a continuous search for what’s ‘cool’ amongst the youth. Since the behavioral distance between the youth and the others in these societies is significant, it’s easy to rally youth around such points of difference.

This model however is at a loss in an environment like India, where everything and everyone is young. India has its largest consuming class population of about 50 million (urban, top three socio-economic classes) in the age-band of 25-45 yrs. But most of them behave more like teenagers who are just about turning 15. In reality, the Indian consumer is precisely 15 years old as that’s how long it has been since Indian markets have been liberalized. With a new found affordability and new avenues of consumption, everybody in India is young. This goes not just for the people but also for the brands. A society held back by scarcity and a self restrained value system built around it, is suddenly opening up to the pangs of desire. In their attempt to be attractive to these consumers with deep pocket, the brands have realized too that being ‘youthful’ is an easy way to go.

But the phenomenon of everybody feeling young and all brands being youthful has the real youth as a casualty. For those in the age band of 15 – 25, the immediately older generation is a competition not only for the brands that they can wear but also the places that they can hangout and the fashionable things that they can do. The truth is that Pepsi in India is fast becoming a family drink and Levis is as much a brand for the intern as a CEO. In the continuity of youth as an age and youth as an attitude, the real youth of India has nothing that they can call their own. The youth in India is thus being squeezed out by the youthful. And that’s leaving the Indian youth wanting for anchors that they can truly call their own.

No wonder, in a country with a median age of 24 years and about 200 million people in the age band of 15 – 24 years, there are no mainstream youth brands. Partly because in terms of sheer numbers and purchasing power, ‘youthful’ is a much larger segment hence always more tempting. As always being only about the youth is a sacrifice and sacrifices in business and marketing are not always easy to make. But more than that many brands who know that they would be happier being more sharply about the youth are not being able to be so, because most youth marketing practices lead to brands that are ‘youthful in character’ than ‘young in motivation’. While youthfulness is a character easy to acquire, being young is about a motivation, which is not so easy to crack.

Designed to be Distant

The traditional marketing paradigm is designed to look at the consumer from a distance. Consumer is another box in any brand model. His identified need gap fills this box. Research thus, is designed to be done from a distance. The consumer is there to be met and be reported about. This frame of reference gets even more pronounced in the case of youth marketing. The awareness in the marketer that the subject of his study is different from him is generally acute in the case of youth marketing. As the reality often is that the marketer has spent at least some if not many demographic years learning the tricks of the trade. But the mismatch in his age and that of his target can often be a subject of nervousness. The starting belief that the target segment is inherently different in the way he behaves makes it imminent that our conclusions about them appear so as well, many a time at the risk of being unreal.

The trap with youth marketing is that we end up treating youth as a different animal. We imagine this guy with tattoos all over his body, multiple piercing and spiky hairs. We try and imagine him to be someone completely distant and different from us. We isolate them and then we micro analyze them, only to say – hey you know what youth likes music. And they like to hang around. But really how different is that from what you and I like to do? Don’t you and I like music too and may be hanging around as well? Just that our hanging around and our music may not be same as theirs. The point is that youth is not a different species to be analyzed through some National Geography lenses. They are perhaps just another generation, who need to be understood from an internal lens than from the outside.

Bridging the Gap

Building a real youth brand in such contexts needs a change in frame. It needs an ability to look at the world from their side up than look at them from our world down. A frame of observation (research) which allows us to experience life, its anxieties and desires from youth eyes, and a way of intervention (brand) which becomes more a part of them rather than trying to fill a gap. If we continue to be at a distance and look from outside, we will stay in the space, which is youthful but not necessarily youth. It’s critical therefore to create a bridge space of interaction between the marketer and the target segment as well as the brand and its audience.

What’s critical also is to look at youth not as a different species, but as just another generation. A generation, which is a continuum of other generations and in many ways, defines itself in relation to them. Being subject to the same social stimuli, but responding in a different way. To be able to sharply understand how youth as a generation is different, we need to look at them in relation to the other generations. After all what makes the youth has to be in many ways what doesn’t make the others!

The Market Model of Co-Creation

This paper draws the principles of mining youth insights and building youth brands in increasingly youthful countries of Asia like India. The framework is inspired by the new market thinking on co-creation as outlined by C K Prahalad in his book, ‘The Future of Competition – Co-creating Unique Value with Customers’.

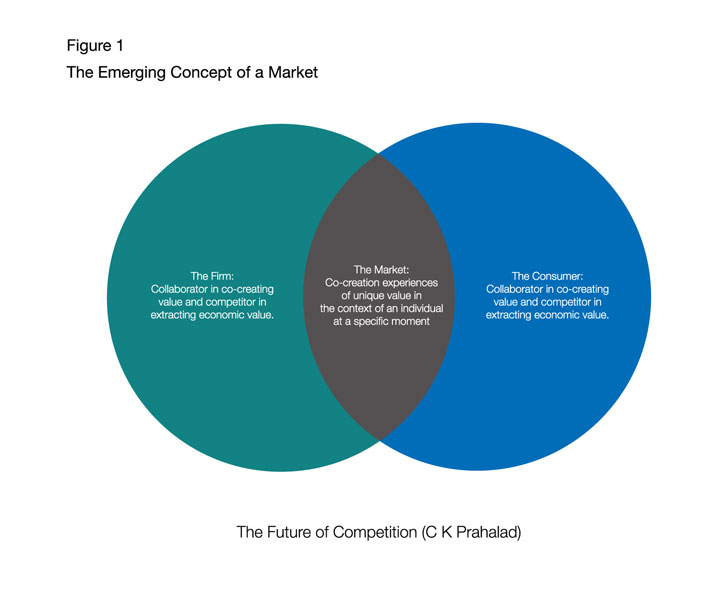

The model ‘Emerging Concept of a Market’ (C K Prahalad, The Future of Competition) suggests that the firm-consumer interaction is the locus of co-creation of value. It proposes that the firm and the consumer are both collaborator in co-creating value and competitor in extracting economic value. This definition of Co-creation converts the market into a forum where dialogue among the consumer, the firm, the consumer communities and networks of firms can take place. It insists that we view the market as a space of potential co-creation experiences in which individual constraints and choices define their willingness to pay for experiences (see Figure 1).

Creating a Common Platform – Participation Labs

The first and foremost implication of this emerging concept of the market is creating a shared space between the brand and the consumer. The act of creating this shared space in many ways has to begin with the act of interacting with consumers to find insights into their lives. Consumer research has to be able to find a framework, which enables an equal interaction. To start with, the research scenario where the researcher is ‘one talking to many’ has to change to the researcher as ‘one amongst the many’. An audience like this can only be understood from their vantage point, and perhaps never from outside.

Implementing this construct on ground had two big limitations. The first one being that the normal recruitment processes used for recruiting consumer groups brought back respondents whose frame of mind was exactly that – ‘responding’. For participation, we needed people who would participate with their lives and help us create the prototype of the brand including the product offering relevant to their lives. The second one pertained to the imagination ability and the interest levels of the recruited respondents. Their commitment to the process was time and incentive bound; their interest levels were therefore limited. Apparently this was not the framework of interaction best suited for creating co-creative spaces with the consumer.

Our key target segment for this project was youth in the age band 15 – 25. We decided to create what we called ‘participation labs’ by getting to them in two ways. First route was to tap the friends of friend’s network. From the youth that were socially known to us, we built a group of friends. The desire and the degree of participation in these cases were high as for them it was a group time with the people that they wanted to hang around with either ways. The second route was reaching out to them in their colleges. Wherein invitation to participate was made through posters put up at the colleges. Those interested were asked to answer certain questions – these questions were designed to test their ability to create and cross connect and their desire to participate in such exercises.

The youth participation labs thus created was used to explore large life themes and hypotheses about their changing behavior. Their minds were also leveraged to come up product and service ideas that came from their own life needs and experiences. While the output from the life themes went more into crafting the brand message, brand relationship and advertising content, the product and service ideas went into the innovation funnel for the future products and service propositions.

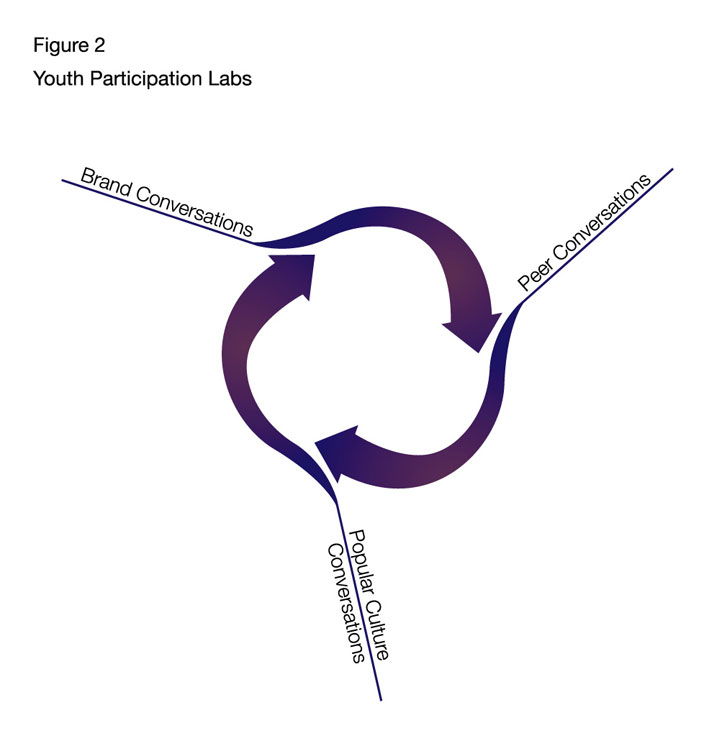

Stimulus and hypothesis from popular culture analysis, observed behavior of the youth and cultural trends were fed into the participation labs. This was done with a purpose of building on them further and finally funneling them into specifics for brand and product purposes. This allowed all the feeds of the popular culture, observational hypotheses and one-on-one conversations to be churned and processed by the youth. The output thus recorded was an insider view of the youth on what they thought and what others thought of them (see Figure 2).

Indian Youth – Key Drivers of Change

Our efforts to understand the youth in India in these ways led us to some fundamental Changepoints. Changepoints as defined at Bates141 are the definitive and the irreversible shifts that are taking place in the society at large – media, politics, the environment, entertainment, marketing and branding, consumer behaviour and attitudes. These Changepoints are fundamental in the way that they define and explain the larger changes in people’s behaviour. Elaborated below are the three-mega shifts that the youth in India are going through today, seen in the context of earlier Indian generations.

1. Discontinuous Ways for Discontinuous Desires

Much has been spoken about the confidence and the ambition of the new India at large and the Indian youth in specific. There is however a difference in the calibration of the confidence that the Indian youth displays today versus that of the larger India. While most of the generations in India have displayed a sense of personal buoyancy in the past decade, they have always kept an eye on the ground. The generation senior to the youth, though desirous of flying has wanted to fly with its feet on the ground. As there always has been this fear of falling, in many ways accentuated by the current slowdown.

The youth in India on the other hand wants to fly without ever looking back at the ground. They want to achieve discontinuous dreams, many of them material like owning multiple apartments, becoming a CEO by the age of 32 and so on. Most of them have entrepreneurial ambitions to start something of their own once they have accumulated just the right amount of experience in a regular job or their family business. The biggest difference that this generation displays is an ability to experiment without a fear of the consequences. They will continuously tell you ‘I don’t regret anything in life’. Our participation labs told us that life is like a Facebook for this generation, where multiple experiences, relationships and parts of their life including personal and professional, connect simultaneously on one platform or portal.

A life of discontinuous desires has meant that it cannot be achieved through linear or square means. Discontinuous desires need discontinuous ways. Whether it’s a pursuit of an entrepreneurial dream, jumping multiple jobs or even careers or managing multiple relationships, the youth in today’s India display an amazing dexterity in managing discontinuity. This has certainly led to many of the old rules of the game getting redefined as the old rules of the earlier generations were designed to maintain continuity and linearity. Playing the new game of discontinuity, the youth in India today have written many new rules.

2. Shifting Locus of Morality

For today’s youth in India, the larger locus of morality has shifted from what was socially appropriate to what’s personally useful. What’s good or what’s bad is no more decided by what others would say, it’s decided by what you want. As the youth in our participation labs put it “we believe in being honest, but only to ourselves”. The value system of this generation is therefore, constructed by themselves. Hence their value system is not something that they have to live up to but something that’s been designed to help them achieve what they want to. It’s a via media to their desires rather than being a destination in itself.

The shifting locus of morality has also meant that a lot of the sacrosanct of the earlier generations has been questioned. For the youth of today’s India putting up a social face whitewashed in goodness is not of a primary importance. In fact small shortcuts, some manipulation, a little greed is ok for them. Some bit of bad is actually good for this generation. As they put it in our participation lab “if you can’t scoop out cream with a straight finger, there is no harm in using a spoon”.

This shift has made itself manifest in the rise of the new anti-hero archetype in Bollywood. At one end there is a death of the quintessential villain, as he existed in the Indian cinema – the repository of all that was socially evil. In an act of reciprocation, the hero of the Bollywood has turned a little grey, cutting some corners at times and not hesitating from pulling a fast one to achieve a milestone in his path to success. There are enough instances of such behavior in most successful Bollywood films of the current years whether it’s the friends acting gay in Dostana to able to rent a flat or the square husband Suri, donning the alias of a flamboyant Raj to woo his own wife in the Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi. The point to be noted however is that all of this is done in jest and overall it’s being cleverer than mean.

3. Seeking Partners in Crime

The youth in today’s India is actually a ‘silver spoon’ generation. Compared to the earlier generations in India, they have it going really good for themselves. Not only have they been born to a time that’s relatively more affluent and buoyant, but they are also making the maximum of what they have whether it is in careers or in relationships. This generation has no baggage of yesterday and has no gaping need gaps as of today. Such a state of its consumer is a nightmare for classical marketing which is designed over the years to identify large need gaps in its consumers and find ways of fulfilling them.

The youth of today’s India is not looking at brands to make them feel liberated or empowered as classical youth marketing is very adept at doing. But what this generation is seeking is a certain legitimization. The rules that they have written in their pursuit of the new game need a subtle endorsement. For after all while they may not have upset the applecart, they have certainly tweaked the social codes to their advantage. The need for this generation therefore is for brands to legitimize their way of life. Not from a pedestal but by being one with them. By playing buddy and being a partner in the crime.

The desire really is for a relationship that’s born not out of hierarchy but empathy. They want to hear a language, a tone of voice, a set of mannerisms that belong to their world and not outside. It’s almost as if they want the brand to be a character amongst them rather than outside them. This is a big shift for a culture like India which scores high on power distance; where people have always sought idols that they can look up to and have always wanted to put people up on the pedestal. No wonder, for the youth of today in India there is no single role model. Their role model is a mish mash of various qualities that they admire in the successful heroes of the society or from their own personal life.

A New Framework for Youth Brands

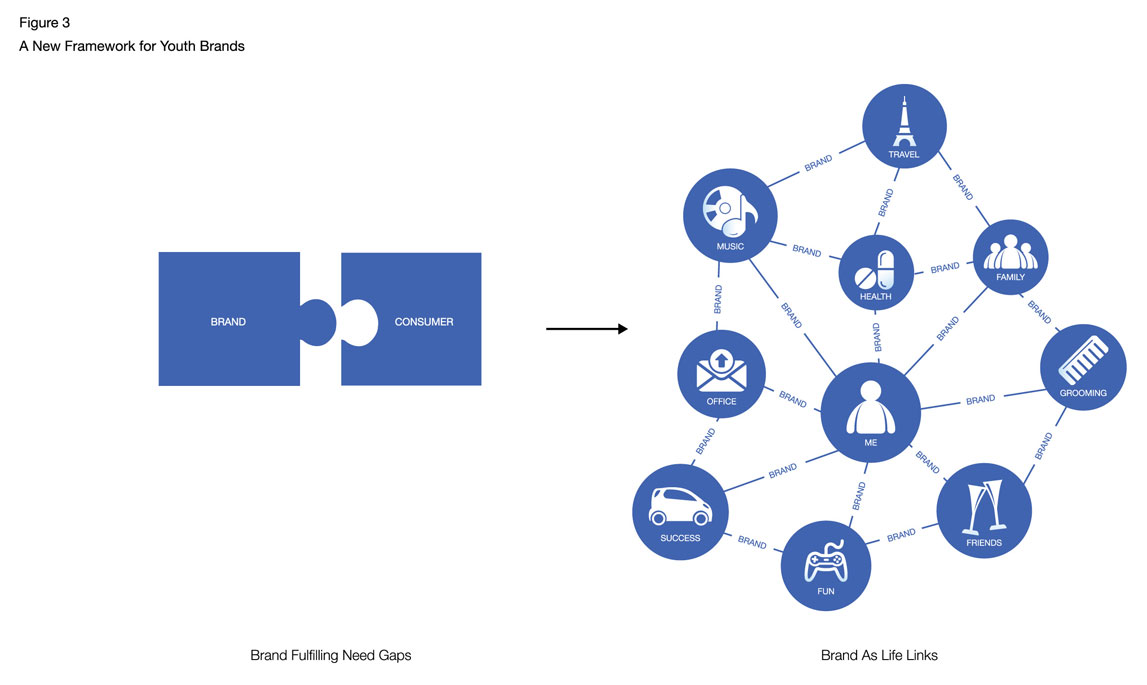

The key drivers of change in Indian youth mapped above clearly point towards the need for looking at youth marketing from a vantage point that’s different from the traditional or even western models of youth marketing. Most brand thinking frameworks look for need gaps and fit brands in them. The truth is that the youth in today’s India don’t really have many big need gaps. Rising affluence and better opportunities have made sure that they have the money, the relationships and the job options that the current senior generation could only dream of. The role for brands in their lives is not to find unmet needs but to find a way to legitimize fulfillment. A brand for this audience has to be built on a model of partnership versus the traditional need gap approach.

Looking at youth marketing from the side of the youth has several implications. Firstly, the brand’s relationship with them can neither be linear nor be one way. The brand has to somehow find a way of being a ‘part’ of the youth’s life. Secondly if the brand has to fit in the life of the youth then it has to find multiple ways of adding value. In many ways the brand has to thus begin to power-up the Facebook life that the youth today is leading. A brand can thus not keep its delivery confined to what its category primarily offers. For example a mobile brand for youth cannot stay happy by simply enabling voice and data connectivity for the youth, which in a traditional marketing paradigm is its primary delivery. The brand has to travel farther and find other links in the web of the youth’s life that it can help maximize.

The proposed brand thinking model for youth especially in contexts such as India and other such Asian cultures have to make the following shifts from the traditional models:

- From the hierarchy of fulfilling need gaps to a partnership of value addition

- From a one way connection to helping maximize several links in his life web

- From being confined to the delivery of the core category benefit to finding multiple roles in his life

Thinking of Brands as Life Links

In the new framework, the brand has to learn to define itself not in terms of a fulfiller of need gaps instead as links in the life web of the youth (see Figure 3).

This framework looks at the brand as a series of links in the life of the youth, in his open system life web, helping him maximize his ecosystem. It asks us to be preoccupied not by what links the brand to the consumer but to be preoccupied by how the brand enables multiple links in the consumer’s life. This in turn means that rather than a singular connect between the brand and the consumer, there are multiple links that the brand maximizes in the consumer’s life. Each brand will therefore have to play multiple deliveries that its category can offer. It’s critical therefore that basis its strengths and what the category enables, every brand chooses which links it will play and how it will do it in a new way.

For instance a youth brand in apparel space may go on to leverage peer to peer reviews on its latest range made available at the brand store, its websites and may be even mobile phones. The brand then is not just plugging into the need gap of looking good or cool but is actually leveraging the idea of peer shopping and helping the youth connect to its community and their opinions through the brand. Similarly a youth brand in snack food could try and leverage their relationships with music and partying, enabling ways to organize better friend’s get-togethers. The brand then is not just fulfilling the need gap of tasty snack on the go, but is actually linking itself to the entertainment network of the youth.

Virgin Mobile India – A Case Study

Virgin mobile is a case, which demonstrates that the biggest role for youth brands in Asian markets like India is not to find need gaps and fit into them but to find life links and be a part of them.

The Challenge

Virgin Mobile as a brand internationally has a clearly identified enemy – the injustices that the mobile consumers are subjected to by other players. An analysis of the tariff structures in the Indian market revealed that the mobile subscribers in India were having it good. High competition and tight regulations meant that there weren’t really many injustices in the category. The brand Virgin Mobile had to thus find a consumer positioning as it would not be possible to fight category injustices.

Virgin Mobile decided to target the 15 – 25 year olds in India. It has globally been the brand for the youth. But in a country where the flavor of the times was young, just being about the youth would not be good enough. How could Virgin Mobile ensure that these brands would not any more be the default choice for the Indian youth? This was the key challenge for Virgin Mobile in India.

The Insight

Our interaction with the Indian youth through participation labs, popular culture mapping, blog analysis etc. led us to a unique understanding of their lives – their relationships, dreams, dilemmas and expectations.

The Indian youth today is retrieving self-space. The youth in today’s India have cracked a unique route between tradition and modernity. They are challenging many of the old tenets of the traditional Indian way of life. Whether its about a blatant craving for fame and money as against the traditional Indian belief that money corrupts, or more edgier things like living-in before marriage, to having multiple relationships simultaneously or jumping jobs in six months. They have taken several status quo beliefs head on and have shattered them. But they are unique and clever in the way that they are doing so without any rebellion or upsetting the applecart.

Evidently, this is not a generation, which wants it persona to be whitewashed in ‘goodness’. As a generation therefore, a little bit of bad is actually good for them. The need for this generation is a certain legitimization of their way of life. For a brand to come and endorse their values, principles and behavior as legitimate by participating in it with the same values, principles and behavior.

The Brand Idea - Bypass the Firewall of Sanctions

Virgin Mobile recognizes that today’s discontinuous desires need discontinuous ways to achieve them. Virgin exhorts the Indian youth to be inventive in their ways, to find new ways around old things. In the same way as Virgin Mobile is challenging the category and its ‘done’ ways to unlock value for the youth. Virgin Mobile will be their partner in the crime, and will exhort them to – bypass the firewall of sanctions.

The Results

Virgin mobile has exceeded its month on month subscription growth rate by 46% during April to June 2008 while the CDMA category grew by 10% and key players like Airtel, Vodafone and Reliance grew by 11 to 12% in the same quarter. Virgin mobile’s scores on young and innovative brands have been far higher than the competition, including those like BPL and Idea who have run campaigns specifically targeting the youth.

Hits to its official website jumped more than 10 times the day its first television commercial went on air. On YouTube the commercial reported views that were 30-40 times higher than those received by competitor’s television ads playing on air at the same time.

The brand has managed to get 65% of its subscribers from the targeted segment of 15 – 25 years. Virgin mobile has 30% higher average revenue per user than the CDMA industry, since youth are heavy users of sms and other value added services. The brand is beginning to be a part of the everyday popular culture with mentions in television shows and general interest articles leading to free publicity.

Conclusion

Applying western models of building youth brands to a country like India leads to a severe disconnect. The inherent assumption of the Western model is that the distance between the youth and its senior generation is wide enough to pit the youth against them and build a brand out of this tension. In today’s India however, the tension between the youth and its senior generation is of a different nature. The case here is opposite to that of the Western context as the new found affluence of the middle aged is making the youth look continuous with the youthful. Thus rather than seeking a celebration or an empowerment for its distance from the rest of the society, the youth in India is seeking to retrieve its space or in other words actually build some distance from the senior generation.

However the road to building a brand, which really connects with the youth from the youth side up rather than the brand side down, is rather less traveled. Most research frameworks are designed to report the consumer as a third party entity. Most brand frameworks have consumer as just another box to be filled with their unmet needs and most senior marketers end up analyzing youth as a separate species as their underlying assumption is that youth is really very different from who they themselves are. As a result they end up building this image of youth who is everything that they are not – a creature with multiple tattoos, body piercing everywhere and dancing to hip-hop everywhere and hanging around in malls all the time.

There is an inspiration in C K Prahalad’s model ‘Emerging Concept of a Market’ in creating a shared, hierarchy less space between the consumer and the brand. The first step of bridging the gap is in the way we interact with consumers to find insights. The need here is to participate in their lives and make them participate in the process of creating the brand by facilitating this equal space. The ‘participation labs’ as we call them were thus created with youth wanting to be a part of such creation rather than those recruited to become respondents. Exploring the world of youth from such a vantage point is the first step of building a brand youth side up.

The world of Indian youth has witnessed fundamental changes especially compared to the previous generations. What was sacrosanct till now has been made fluid. Their desires are discontinuous, their morality is self assessed and they are seeking more a partner in crime than just need gap fulfillment. A consumer segment like this needs a framework of brand building that too is non-linear and non-hierarchical. A brand framework, which is designed to locate the brand into the life web of the youth than plug into it from outside.

The new framework of brand thinking thus needs a shift away from need gaps to life links. As against the traditional paradigm of brands where the primary preoccupation is the link of the consumer with the brand; this framework proposes that we worry more about how many links the brand enables in the consumer’s life. From a singular point of connect with the consumer to a role in his multiple life links. From leveraging the main category delivery to thinking how else can my category power up the life web of the youth. Creating this bridged space between the brand and the youth is actually a journey, what’s important is that we begin with this intent in our minds.

(This paper was first presented at Esomar Asia Pacific Conference)

No Comments